Native American Literature: A Very Short Introduction - Sean Teuton 2018

Oral literatures

Long ago in this world there was no land but only water. Above in the Sky World a leader’s daughter lay gravely ill, but a healer dreamed the means to save her: the people must fell the tree that provided the nation’s food, then lay the girl at the foot of the tree. After they did so, however, a young man stormed forward. He said that it was wrong to destroy their food source to save their leader’s daughter, and he kicked her into the hole left by the uprooted tree. Down she fell, but she was caught by a curious bird just before hitting the water. The bird grew tired of carrying her, but a great turtle took its place. After much discussion, the animals decided that Sky Woman must have land on which to live. Toad volunteered to dive down and retrieve mud to mound on Turtle’s back. Thus humans arrived on the land we now call Turtle Island.

Though variations on this “earth diver myth” have circulated across North America for centuries, they did so orally. Native Americans carefully trained their memories to record and transmit vast bodies of knowledge verbatim because, in an oral society, the known universe always stood only one generation from loss. Indigenous tales instruct in ethics, ecology, religion, or governance; still others record ancient migrations, catastrophes, battles, and heroism. Oral literatures often form the basis of Native American writing to this day, and so they begin the story of Native literature in North America.

For centuries Iroquois people have experienced this story differently from the way we do as we read it from the printed page: they have long learned from Sky Woman’s experience in their lodge of worship, the Longhouse, orally in an indigenous language, and among generations of related people using songs, rattles, and drums to enrich the tale’s reception. Listeners to Sky Woman’s story do not expect originality, but often they do offer varying interpretations of the story’s meaning and ordering of the world.

Oral literatures grow from differing landscapes and their forms of life. Native Americans of the Pacific Northwest describe heroes such as Salmon Boy, who springs from a caught fish; on the Great Plains White Buffalo Calf Woman, and in the Southeast Corn Woman stand for sustenance itself and thus promises life. Despite their differences, oral literatures usually communicate a wish to live intimately with a unique ancestral land and its creatures, a commitment to a proper relationship with that land and its broad community, and a belief in the power of story to achieve this accordance. In a process that scholars term “world renewal,” storytellers reaffirm their audiences’ very understanding of their known universe.

Sky Woman helps build such a world. Humans accidentally enter another realm, where they would only drown without the help of the animals. Listeners learn they originate in the sky and must adapt to the demands of this other world. They share the leader’s excruciating ethical dilemma: whether to lose his daughter or starve his people. He elects the former, only to have his authority rightly challenged by a younger leader. The story of Sky Woman thus conveys lessons in hierarchy, democratic community, and adaption of landscapes. That the animal people save and nurture Sky Woman invites trust in the earth’s providence and affirms responsibilities to nonhuman populations. The first human is a solitary woman, thus declaring the centrality of women to Iroquois and other woodland peoples, who traditionally trace their descent and locate their homes through women. Such ancient relationships among communities, genders, and animals must be honored with trust and care through reciprocity. In telling and retelling the story of Sky Woman, Iroquois people hallow their relationship to this world while maintaining kinship with the spirit realm in the sky.

One day long ago a boy and his seven sisters were playing near the foot of a mountain. Suddenly the boy began grunting and scratching, and before their eyes he transformed into a bear. Terrified, the sisters climbed up the mountain, and the bear clawed after them, scoring the mountain with his fierce claws. Up and up the girls ascended until they reached the sky, where they remained as the stars of the Pleiades. The boy bear departed but the strange mountain known as Bear Lodge remains, tying the Kiowas to their migratory landscape through story. To this day they tell this tale to remember that they will always have relatives in the night sky. The storyteller seeks to depict this archetypal landscape, where the land and its inhabitants exist in complete order. Thus is Native American oral literature built not on fiction but indeed on truth, though of a special kind. In many indigenous philosophies, truth cannot be factually proven. Unlike many of us, Kiowas do not ask whether a boy really became a bear; rather, they confer truth by the understanding of the world that the story enables and protects. Often within this task the speaker can nonetheless improvise: some performers contend that Sky Woman was never kicked but fell, or even jumped. In this way, oral literature guards against dogma and sustains itself through adaptation.

Other indigenous creation narratives serve to categorize the world, its parts and interconnected taxonomies, through observation and testing. A Cherokee narrative posits a world beneath our own that one may reach through springs. They know this world experiences seasons opposite to ours because, whereas in summer a spring’s water feels cool, in winter it flows warm.

Still other oral narratives advance a carefully prescribed ethics. For Blackfeet, Feather Woman married Sun and went to live with him in the sky. She missed her home terribly and one day, against Sun’s threats, pulled the sacred turnip and climbed through the hole in the sky. Though sharing traits with Sky Woman’s story, Feather Woman’s narrative warns the people to be content with either this world or the spirit world, to honor the space between life and death. A long time ago some Sioux hunters saw a white buffalo calf transform into a beautiful young woman and approach them. When one lustful hunter tried to seize her, White Buffalo Calf Woman turned this man into a skeleton before the others’ eyes, then communicated to his more respectful compatriots the sacred pipe ceremony. While this central story to the Sioux no doubt explains the origin of the pipe, it also teaches respect for women.

Oral philosophy

Nineteenth-century ethnographers often interpreted oral literatures through the era’s Social Darwinist assumptions, as evidence that Native Americans existed “static” in a previous, “primitive” stage of human development up from which they could not “evolve.” We now know that nothing could be further from the truth, that the oral tradition’s ever-changing body of communally derived philosophy, in fact, challenges the very notion of stasis. Old ways and values have always required collective reflection and revision to thrive in an always changing world, and in today’s world speakers transmit old tales both orally and in writing, and increasingly through graphic novels, film, and digital media; stories remain simultaneously new and authentic, and they continue to mix the real with the fantastic. Native people thus consciously shape their bodies of knowledge with new practices, values, and even languages, specifically to build ancient indigenous worldviews. For this reason we may best understand the growth of Native American oral literature as a process wherein performers consciously incorporate new conventions—even contradictory versions of a particular piece—within a flexible body of thought. Here knowledge is not the final identification of an unmediated truth, but an ongoing process in which storytellers and listeners may offer multiple perspectives. In this manner oral literature draws Native Americans into a culturally regulated center of knowledge.

The world-building power of oral literature relies on a particular conception of the imagination. Among many Native American peoples to imagine is not to see an illusion, but to manifest that which once did not exist. It is this understanding of the imagination that differs from narrower notions of the term. Popular usage often equates imagination with childish fantasy, or even with delusion. In its scientific and artistic use, however, imagination invites our capacity to see beyond our apparently limited world to solve problems or create art. Community members employing this version of the imagination to interpret their shared place in the land do not unconsciously rehearse a concretized script. To the contrary, they willfully reinvent their very world and their view of how best to belong to it.

Some writers describe this process as one that aligns two landscapes, one external and another internal. To many Native Americans, the external landscape includes not only the many elements of a certain region, such as the shape of a mountain or a bend in a river, the colors of rocks and soils, and its specific varieties of plants and animals, but also the subtle relationship among all elements. That totality might include the way a spring wind after a cool rain causes dogwood flowers to tremble, or the sound of shale sliding down a red clay canyon as bighorn sheep descend to greener grass in late winter. Native people tend to hold this external landscape and its close relationships as an inviolable order where the universe is always whole, pure, and complete.

The interior landscape is that place where perceptions, ideas, and beliefs reside. Because Native Americans are often profoundly influenced by their ancestral homelands, this internal landscape bears the above relationships and, in fact, forms a mirror-like reflection of that exterior landscape. Even among Native people, however, such template-like overlays of mind and land are viewed as ideal: that perfect state of being in which one exists in balance with these two realms, a state often described as harmony or beauty. In pursuit of this harmony, a singer or storyteller invites communal participation in a people’s oral literature, where, if successful, listeners discover a profound sense of well-being and delight. This state of bliss between mind and land creates mental, even physical, wellness. Many Native Americans also view narratives to exist in three epochs: a primordial time when the world was young, godlike spirits moved about, humans still were not fully formed, and animals were humanlike and could even speak; a transitional time, when the land settled into its present existence and life forms became more assigned to their present condition; and historical time, when Native Americans can recall through historical memory events such as migrations, wars, and great leaders, and, of course, vernacular or humorous tales.

To align these interior and exterior landscapes, Native Americans often enlist ritual dramas. These include narrative and song but can also include oratory, through which a nation may attempt to control natural and supernatural forces, as in the request for rain, for instance. Such dramatic performances, delivered in special archaic language and style, can be fabulously creative, as in the Pacific Northwest, where performers don costumes that transform them into deities as they enact the story of origin. Navajos maintain a large body of ritual dramas, often to heal the ill. In the Night Chant a healer leads a ritual that begins at sunset and ends eight and a half days later. For the first four days, songs help to purify the afflicted. At midnight on the fourth day deities descend and touch the sick person, to impart their power. On the ninth day the healer calls the thunder; the songs from the previous eight days are repeated throughout the final night. At sunrise on the tenth day the afflicted person faces east and is healed. Consider this portion of a prayer from the ceremony’s third night of purification: “Happily may I walk. / Happily with abundant dark clouds may I walk. / Happily with abundant showers may I walk. / Happily with abundant plants may I walk. / Happily on a trail of pollen may I walk.” In the repetition of key features that suggest emotional restoration and natural replenishment, the singer requests a healthy, mobile body defined by graceful movement over a verdant land. In other ceremonies such as the Iroquois Condolence Ceremony, ritual drama restores the coherence of the confederacy on a leader’s death. Society here becomes a grieving widow whose eyes are filled with tears and whose throat is clogged with ashes from a dead fire in a dark home. Such death and grief threaten insanity, and so the oration washes the eyes of the grieving, in the metaphor that sustains this extensive ritual drama.

Because they form such a part of narratives and ritual dramas, indigenous songs comprise the largest part of oral literatures. Navajos pray by singing, and they strengthen their prayer-songs with melody, rhythm, and multiple voices. Other Native American peoples turn to song when words alone are not enough to complete a prayer. Among Salishes, drums or rattles usually accompany songs taught to a singer through contact with supernatural forces.

Among Papagos, one must perform an act of heroism then fast for a vision that may contain an empowering or supernatural song. Among Hopis and Shoshonis, songs belong to the group as a whole, but for Papagos, families and even individuals can own and transfer songs. Because songs serve to restore indigenous minds to the order of ancestral lands, they often invoke an enchanted landscape, as in this Yaqui deer song: “You are an enchanted flower wilderness world, / you are an enchanted wilderness world, / you lie with see-through freshness. / You are an enchanted wilderness world, / you lie with see-through freshness, / wilderness world.” While some songs invoke the land’s mystical power, others celebrate major events such as naming, puberty, death, and remembrance. This Tlingit song for mourning compares the departed to a drifting log: “I always compare you to a drifting log with iron nails in it. Let my / brother float in, in that way. Let him float ashore on a good sandy / beach.” The haunting image imagines a shipwrecked brother lost at sea and finally moored in a way that brings peace to mourners.

A related genre can be found in Native American speech or oratory. Europeans have long admired indigenous speaking abilities, and training to speak publicly was a part of the early education of many Native peoples. Recognizing this artistry at surrenders and treaty gatherings, Europeans began to translate such speeches, which were often elegies. Such translations, however, differed at times from the original statements. For this reason experts often view translations of elegies nostalgic about indigenous defeat and disappearance with an appreciative though discriminating eye. Through oral enactments found in story, ritual drama, song, and elegy, Native Americans renew relationships with each other, with other creatures, and with the land. Though we should not assume a seamless continuum between oral performance and contemporary Native literature, we might place oral literatures at the heart of plans for world renewal, from colonization to the present.

Heroes and monsters

The trouble started with a jealous Sun. When she daily passed under the rim of the bowl in the sky, the people never greeted her but made ugly faces when they squinted. She complained to her brother Moon, who replied that the people smiled up at him every night. Angrily she shone down on the people, and the people suffered and died under her heat. Desperately they called on friendly deities, the Little Men. The Little Men plotted to kill Sun when she visited with her daughter at midday. They turned three humans into snakes and sent them up to wait at the door of Sun’s daughter’s house. The door opened and Copperhead struck—killing the daughter by accident. Sun hid in the house and grieved, and now the people suffered not from heat but from utter darkness. The Little Men advised that the only way to bring out Sun was to bring back her daughter from the Darkening Land to the west.

The people selected seven men, and the Little Men told each to carry a sourwood rod. They were instructed that, when they found Sun’s daughter dancing they must strike her until she fell from the circle. They should push her into a box and carry her to her mother, Sun. They must never open the box even a crack. For seven days the men walked until arriving at the Darkening Land, where they did find the dead dancing. When Sun’s daughter danced by they struck her seven times before she fell, then quickly dropped her in the box and fled unnoticed. On their trek east she wept from within the box. The girl cried for food and then she begged for air; she said she would soon die. Would not they open the box just a crack? The men relented and opened a slit in the box, then heard a whoosh and saw a redbird stream by. They returned home to find the box empty, and for their failure humans cannot recover their friends from the Darkening Land. Sun continued to bow her head and cry, and her tears caused great floods until the people sent dancers up with songs to entertain her. At last when a drummer changed the song, Sun looked up, saw the beautiful dancers, and finally smiled.

Perhaps second in importance to the origin story within oral literatures is that of the culture hero. In this Cherokee story, in some primordial time the people suffer a misunderstanding with their deity Sun. For their foolishness they are made further to anguish. Only a special person, often divinely chosen, is capable of questing to other mysterious worlds, accomplishing feats or battling monsters, and returning with the resource to save the people—often it is fire or water. Here, the Little Men, though divine, try and fail, indeed worsen the situation with Sun. The bungled plan can be repaired only by human heroes. They dare travel well beyond their known world and, in the longer epic, encounter strange people and stranger customs, dance with and trick the dead, and transgress Sun in capturing her daughter. Like many heroes the world over, these Cherokee heroes bear a tragic flaw. They defy the Little Men’s instructions and open the box, freeing the girl and thus failing to appease Sun. But this narrative also holds a lesson. Readers no doubt share the torment of the men when they must hear the haunting cry from a child trapped in a box. The men’s compassion bursts forth and they free her, allowing listeners to ponder when we should or should not compromise our humanity for the sake of a mission. Last, only dance and song end Sun’s grief, reminding Cherokees that world renewal—like story itself—ensures lasting resources like Sun. Today Cherokees still dance about the fire, the embodiment of Sun, to help her raise her head and smile.

In their ability to travel to unknown lands, heroes celebrate a fundamental quality among many Native peoples that, on first thought, may seem to contradict the creation narrative itself. If origin narratives confirm ancestral place, would not travel risk its undermining? Hero narratives, however, may be understood to complement oral emergences from ancestral lands by inviting indigenous minds to think beyond familiar environments and investigate other worlds where one learns from strange places, then returns home to offer that new knowledge to the people.

Long ago when the world was still dark, Giant disguised himself in a raven skin and left the Sky World. His father gave him a stone that he dropped into the sea, where it rose into a rock on which he landed. He flew to the mainland and scattered salmon roe and trout roe and a sea-lion bladder full of fruits to enrich the earth. But the world was still dark except for a few stars in the night, and the people could barely see to gather the food. So Giant decided to return to the Sky World to steal the light. He put on his raven skin and ascended, squeaking through a hole into the sky, then removed his disguise and waited by a spring near the house of the Sky World’s leader. Soon the leader’s daughter came to fetch water. Giant transformed himself into a cedar leaf and floated on the water, and the daughter scooped him up and drank. By and by she was pregnant and bore a child who cried day and night to play with the box in which the leader kept the daylight. After a few days of play, the baby (who was Giant of course) snatched up the light and fled for the hole, donned his raven skin, and flew to the mainland, where far below some men were fishing. Giant asked for a fish but they called him a liar, recognizing him as Giant merely disguised as a raven. Giant then threatened to break open the box. They refused, he broke it open, and light burst forth throughout the land.

Tsimshians retell this hero narrative of Raven to recall not only how the world was made but also the heroism that enabled it. Here the treasured resource of light itself, as in the Cherokees story, involves a theft. And like many other heroes of Native American oral literature, he moves from the Sky World to the earth world, from bird to human, and man to child, through a symbolic rebirth. In many such stories cunning, deception, and theft win the day, to confirm persistence of folly and subversion within even the most divine events.

In other such narratives heroes possess rare talents. A couple once had a child who seemed old beyond her years, and who sat day after day creating the most beautiful garments made of porcupine quills. On their completion she packed them up and, despite her parents’ refusals, walked to the horizon. Days later she came upon a strange lodge, entered, and unpacked the seven sets of clothes before a boy with a mysterious medicine. Soon his six brothers returned home to find their handsome clothes. Perhaps jealous the buffalo people again and again attacked the lodge to demand the boys return their new sister, but they refused. When they would surely be destroyed, the brothers called on their youngest to use his medicine. All climbed a tree, and the buffalo rammed it, nearly knocking it down. The boy shot a magic arrow into the tree and it began to grow. He shot another arrow and again it grew. On the fourth arrow the tree had reached the clouds, where all jumped free. The little brother then turned all into the stars of the Big Dipper. In hero narratives such as this Cheyenne story, the child hero is preternaturally talented, even to the point of defying her parents or leaders. So doing, these heroes model a pattern of individual dissent from the greater community, but which ultimately heals, saves, or imparts new knowledge to that community.

But what would such heroes do without their monsters? Long ago the land became overrun by war, and people starved and grew miserable. Many lost their humanity and turned cannibal, preying on their former friends. Peacemaker set out to end the violence and bring the people together under one longhouse. On his travels he came upon a lonely cabin, climbed the roof, and looked down the smoke hole to see a snake-haired man stirring a pot filled with human flesh. Peacemaker gazed into the pot and saw the reflection of his own face. The cannibal then peered into his steaming swill and saw Peacemaker. It was not his own hateful scowl, but a clear-eyed and handsome face. In that moment the cannibal read in those pure features who he had been and could be again: a fully human being who reasoned beyond self-interest for the good of all. Peacemaker climbed down from the roof, entered the house, and soon brought the cannibal to what Iroquois people call the “good mind.” To Iroquois people such a story confirms the view that monsters display the ugly side of human nature, but that even the most hateful can be returned to community.

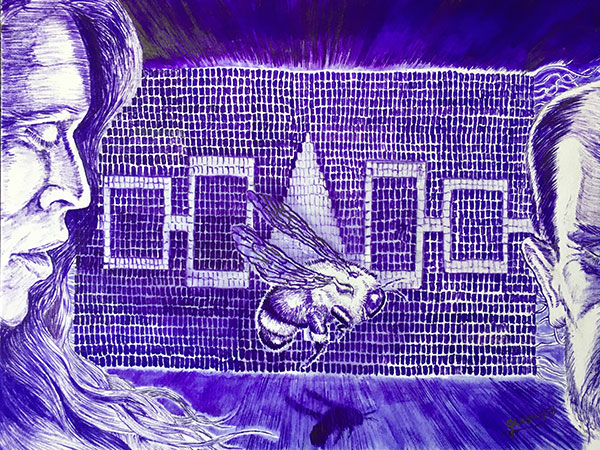

3. This contemporary depiction of the Hiawatha wampum belt, Words and Memory, Pollination Understands Movements, by Eric Gansworth Sˑha-weñ na-saeˀ, retells the story of Peacemaker’s creation of the Iroquois Confederacy. Each square represents a nation, with the tree of peace and fire at the center.

Trickster teachings

In what are often called trickster tales, indigenous oral literatures employ a crafty character who threatens moral tenets, defeats enemies with cunning and deception, besmirches the sacred, and even refuses to die. In the Southeast he is Rabbit, near the Great Lakes he is Nanabozho, on the Great Plains he is Spider, on the northern plains Old Man, in Canada he is Wolverine and Jay, in the Pacific Northwest he is Raven, and in the Southwest and plateau region he is Coyote. Wherever she or he operates (among Hopis she is usually female), Trickster entertains with uproariously bad behavior that listeners consume for pleasure. Still today at the bare mention of Coyote Native Americans might burst into laughter. But why is Trickster such a part of indigenous creation narratives? With folly and blunder, profanity and immorality, he expresses that other human urge toward chaos that is also potentially wildly productive. In this way Trickster brings balance to the Native cosmos.

They say that long ago a terrible winter was causing a famine in the settlement. One by one the people starved and died, and their relatives summoned the last of their strength to hoist their bodies onto scaffolds for burial, as was the custom. Coyote came loping through the deep snow, starving like the people. He stopped at the cemetery and began to sniff around the scaffold, when a dead person spoke to him, inviting him to leap up on the scaffold and visit. The rotting body asked how the body smelled. Coyote replied that he smelled like a delicious rabbit stew. Coyote licked the body. The dead man asked him again how he smelled, and Coyote said that he smelled like a savory chunk of deer meat. Coyote nibbled on the body. Again the dead man asked, and Coyote mumbled that he smelled like a delectable pile of buffalo ribs, and Coyote tore into the putrid flesh. In this manner Coyote ate until the snow melted and the trees flowered. In his shiny, fat coat Coyote lay in the sun beside the pile of chewed bones, when again the dead man asked how he smelled. Coyote jumped up and snarled that he smelled like nothing but a worthless, stinking corpse! Enraged, the skeleton suddenly stood and chased Coyote into the sunset.

This Winnebago story uses dark humor to invite listeners to meditate on a serious moral issue. Today’s readers might struggle to imagine famine but, as this story is very old, it no doubt hearkens to a time when it was often on the minds of those suffering a long winter with dwindling food stores. Coyote thus warns community members about the temptation for ethical transgressions in desperate times. In the story Coyote in his gluttonous, selfish imagination, wishes to believe that the corpse is legitimate food, and even befriends it. When winter subsides and food is plentiful, however, Coyote betrays his friendship. In this manner the Trickster narrative, through humor and even horror, invites listeners to consider the darkness in their own humanity.

Yet while Trickster displays the worst of human behavior, he as often shows Native Americans how to be courageous and cunning to solve daily problems or even to resist attacks on their very lives. Coyote was walking one day when he ran into Old Woman, who said that he should be careful: there was a giant nearby. Coyote boasted that giants did not scare him, though, in fact, he had never met one. While whistling a tune he found a fallen branch and scooped it up for a club with which to kill the giant. Soon he entered a cave and stumbled upon a starving woman who pleaded for food. She told Coyote that he had entered not a cave but the giant’s mouth. Soon he found other people trapped in the giant’s mouth, and the woman told him that there was no escape, as the giant’s belly was as big as the entire valley. Unfazed he travelled to the giant’s belly, then took out his knife and cut meat from its walls to feed the trapped people, who had never thought of that. Now fed, the people asked Coyote how they should escape the giant. Coyote concluded that he would stab the giant in the heart. Looking about he saw a distant volcano, and surmised that it was the giant’s heart. Coyote stabbed and stabbed the giant’s heart, warning the people that when the giant began to die there would be an earthquake and the giant would open his mouth. The volcano began to erupt and the lava, the giant’s blood, began to spew forth. The giant opened his mouth and the people escaped, thanks to Coyote.

In this final Trickster story told among Salishes, Coyote is a strategist who sees beyond immediate perceptions to solve greater problems: the starving people do not think to look about them to gain a more encompassing picture of their troubled land where giants or invaders rule. With his gift of insight and his sneaky and plotting nature Coyote saves the world.

4. On the seal of the Massachusetts Bay Company, an Indian pleads: “Come over and help us.”