Introducing Literary Criticism A Graphic - Owen Holland 2015

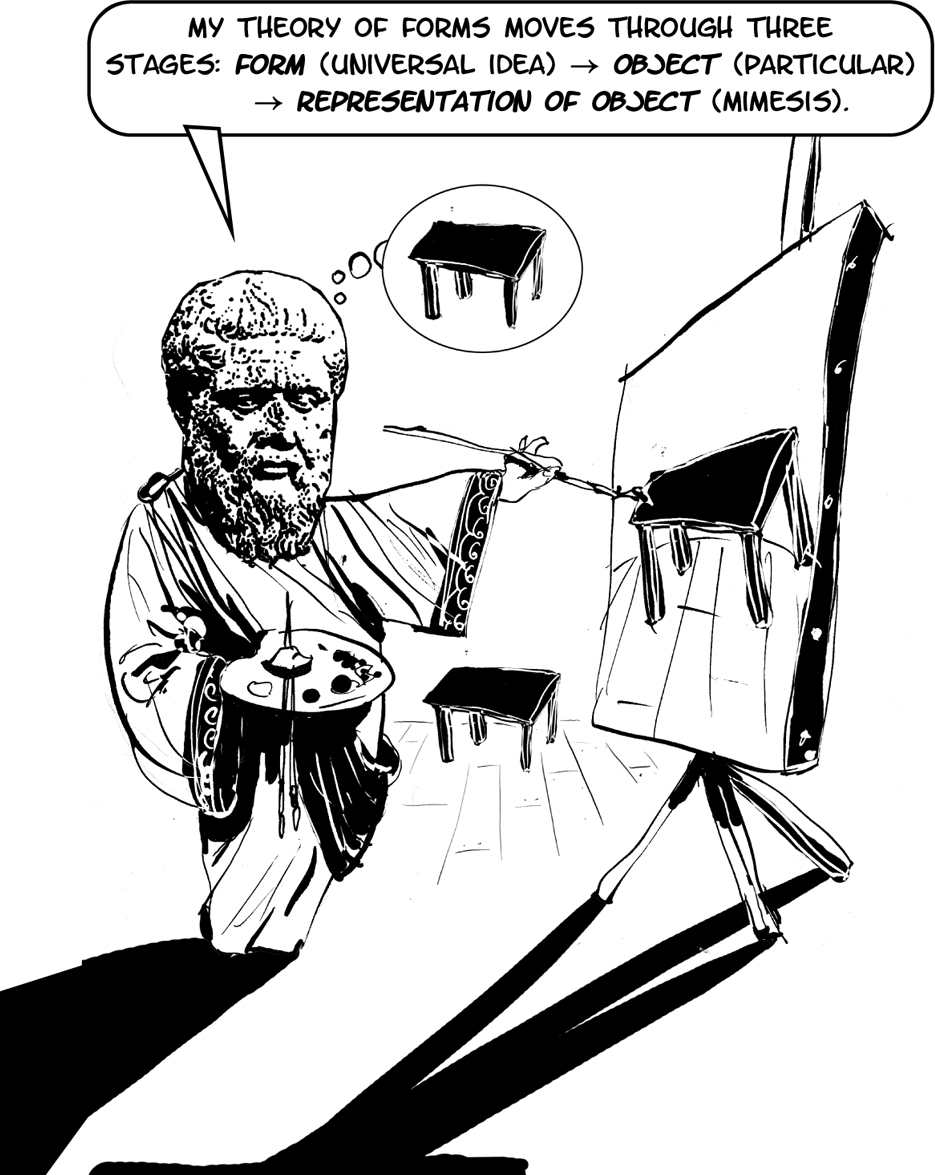

The Theory of Forms

The decision to exclude poets from the republic is based on Plato’s suspicion of mimesis, or imitation, which is regarded as an artificial, or untruthful, deviation from the true essence of things. This is based on Plato’s theory of forms. A poet, unlike a maker of tables, for example, creates only second-hand representations. The poet’s imitation of, say, a table is, for Plato, an imitation of an imitation, insofar as the table-maker’s table is itself only an imitation of the essential, or divine, form of the table.

My theory of forms moves through three stages: form (universal idea) → object (particular) → representation of object (mimesis).

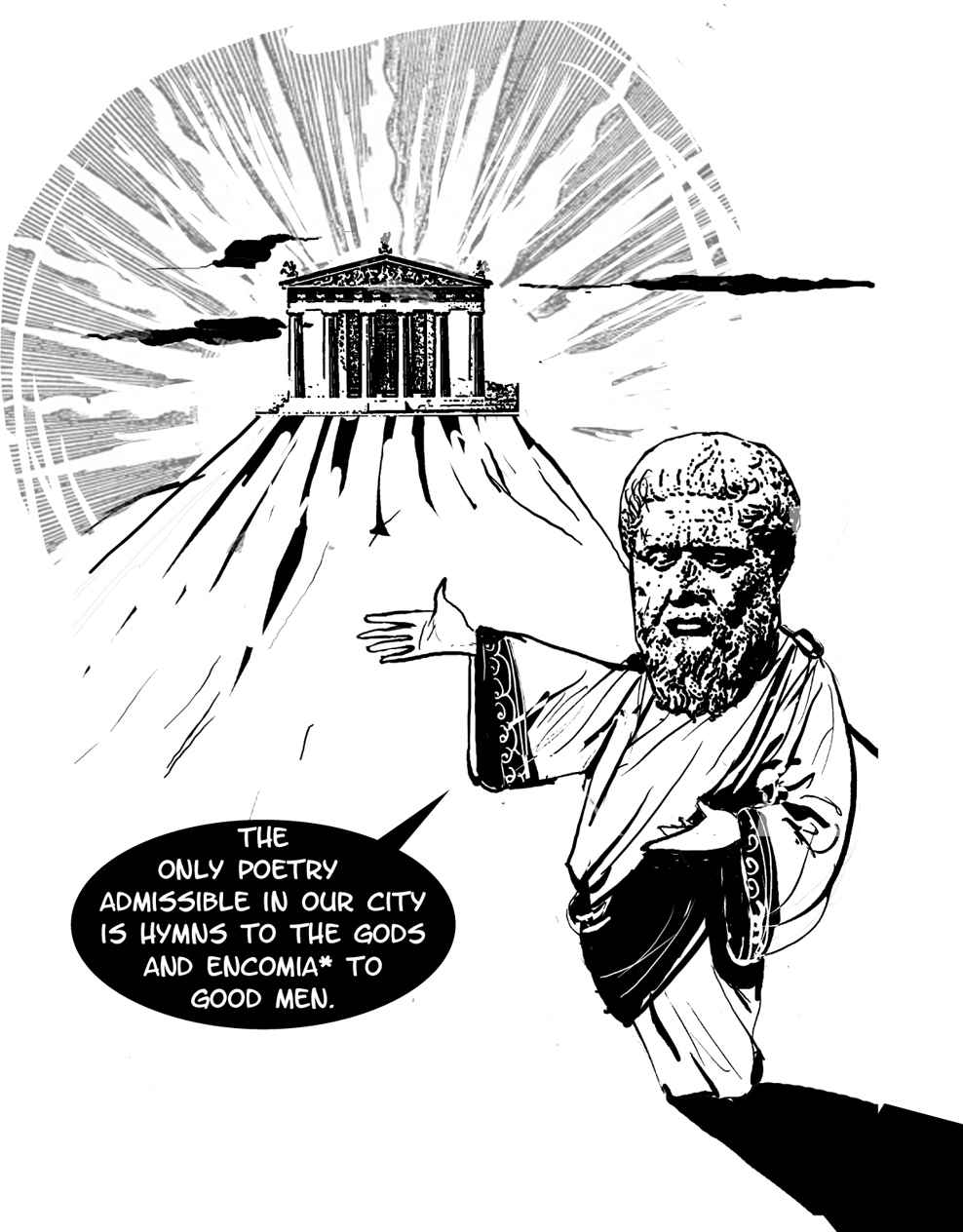

Plato also worried about the extent to which poets create inaccurate (and blasphemous) representations of the Greek gods, citing examples from Homer (ca. 8th century BC) and others, which might disrupt the smooth functioning of the ideal state. Similarly, because poetry stirs and excites the passions of those who hear it, poets might weaken the resolve and self-control of the city’s soldiers and guardians. Plato’s views about the function of poetry were thus very restrictive.

The only poetry admissible in our city is hymns to the gods and encomia* to good men.

Plato wanted a strictly useful poetry, subordinating the demands of artistic autonomy and independence to the greater good of the polis, or city-state. To many readers, his comments have often seemed like an argument for censorship. They can also be interpreted as part of a more playful and long-standing rivalry between the relative claims of poetry and philosophy as a route to truth.

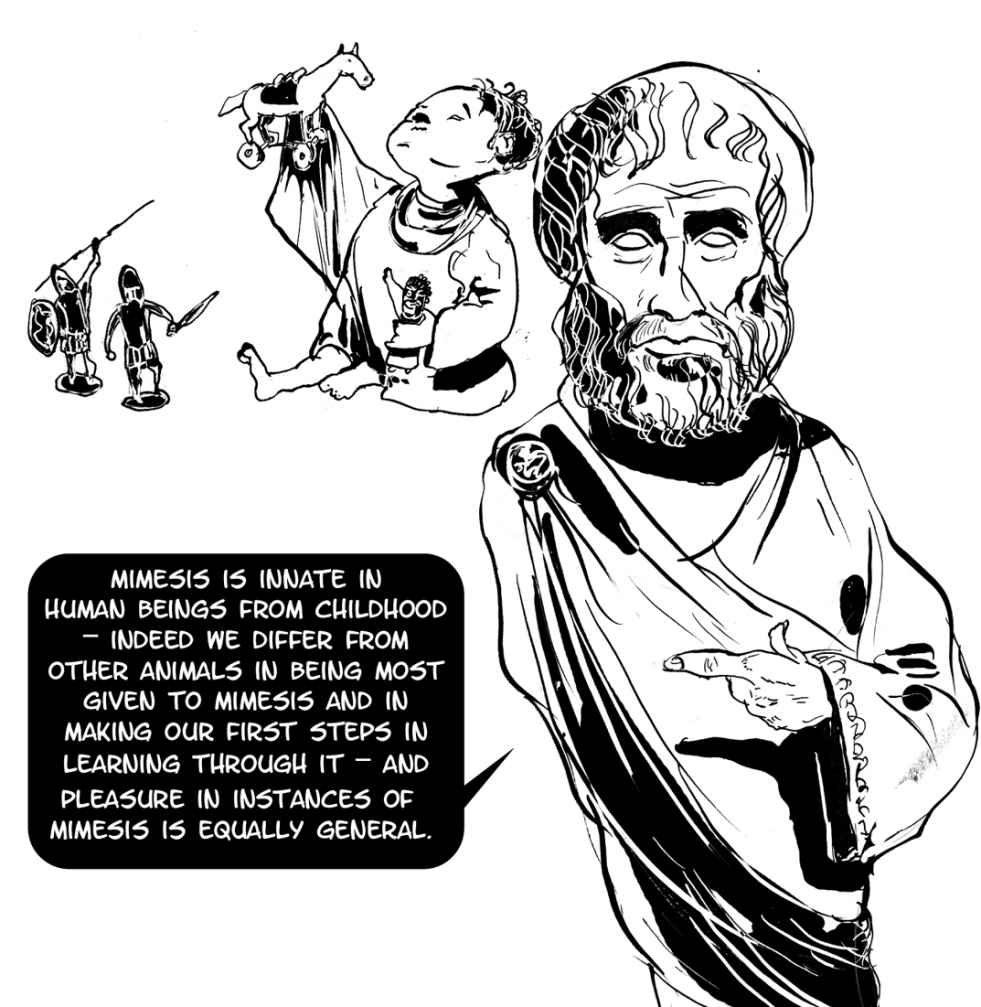

By contrast, Aristotle (384—322 BC), in his treatise on Poetics, defended the mimetic arts — particularly epic, tragedy, comedy and dithyrambic*, and most music for the flute and lyre.

Mimesis is innate in human beings from childhood — indeed we differ from other animals in being most given to mimesis and in making our first steps in learning through it — and pleasure in instances of mimesis is equally general.

Aristotle’s treatise delineates the rules, derived from nature, governing the mimetic arts, including sections on the construction of plots in tragic drama and how to go about answering criticisms of Homer. Aristotle defended mimesis because it is a cause of pleasure, against Plato’s stricter focus on usefulness, linking the pleasure-giving aspects of mimesis to its teaching function. Aristotle’s views of mimesis, particularly tragedy and epic, had widespread influence during the European Renaissance in the 16th century and beyond.