Introducing Literary Criticism A Graphic - Owen Holland 2015

Feminism

“Second-wave” feminist criticism emerged and flourished in tandem with the social movements of the 1960s. This critical movement focused attention on the representation of women’s experience in literature, particularly the novel.

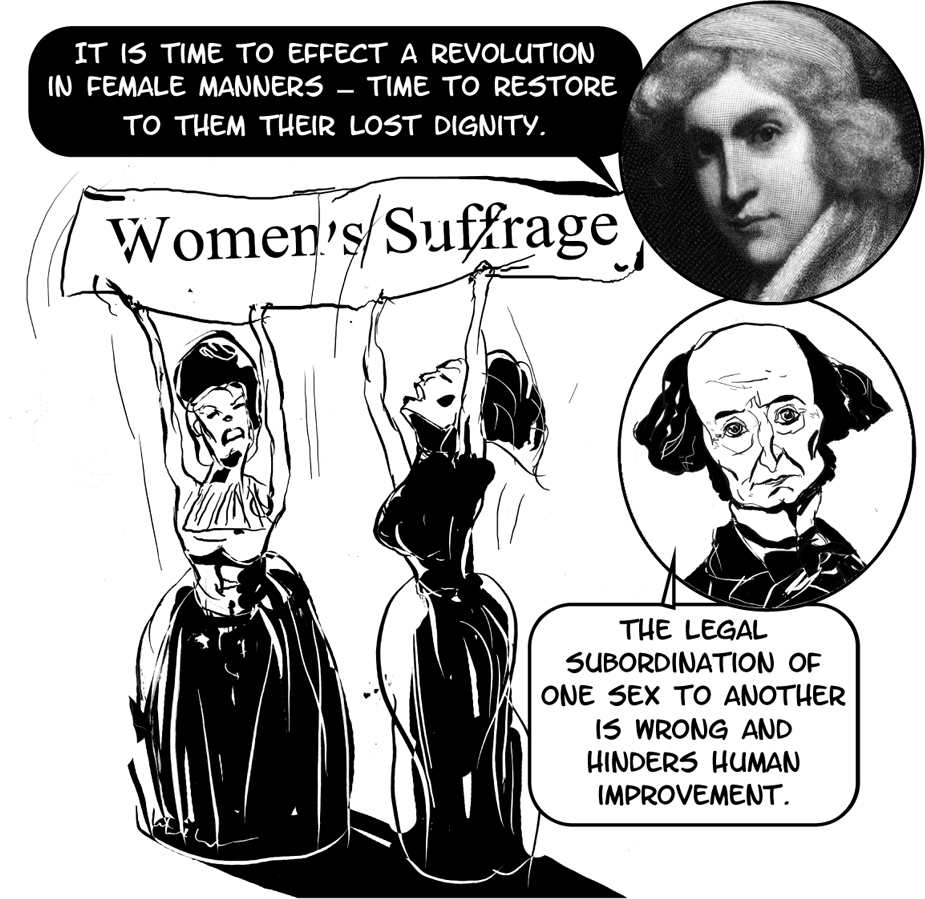

Many second-wave feminists also sought to reengage and reinterpret the critical legacy of “first-wave” feminism, which is strongly identified with (but not reducible to) the 19th- and early-20th-century struggle for women’s suffrage.

The ideological origins of feminism and the struggle for women’s liberation are often traced back to Mary Wollstonecraft’s (1759—97) A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) and John Stuart Mill’s (1806—73) The Subjection of Women (1869).

It is time to effect a revolution in female manners — time to restore to them their lost dignity.

The legal subordination of one sex to another is wrong and hinders human improvement.

The influence of second-wave feminism within literary criticism was most pronounced in two areas:

1. Questioning and exposing the phallocentric (male-dominated) bias in mainstream culture

2. The critical recovery of overlooked female writers and the overlooked tradition of women’s writing.

Kate Millett’s (b.1934) Sexual Politics (1969) and Elaine Showalter’s (b.1941) A Literature of Their Own: British Women Novelists from Brontë to Lessing (1977) were influential in anglophone criticism in both confronting patriarchy and elucidating the existence of an alternative tradition of women’s writing. Millett offers a strident critique of the misogynistic sexual politics of four 20th-century male writers: D.H. Lawrence (1885—1930), Henry Miller (1891—1980), Norman Mailer (1923—2007) and Jean Genet (1910—86).

Mailer’s work displays a reactionary sexual attitude that erupts into open hostility.

Developments in French feminism had been influenced by the publication of Simone de Beauvoir’s (1908—86) The Second Sex (1949). This landmark book questioned the social construction and representation of gender roles.

Later departures formed part of the atmosphere of revolutionary upheaval sparked by the events of 1968 and the post-structuralist concerns with a transformed conception of human subjectivity and signifying practices.

Hélène Cixous (b. 1937) coined the term écriture féminine (literally translated as “feminine writing”) in The Laugh of Medusa (1976) to refer to a kind of writing unmarked by the traces of phallogocentric discourse. Phallogocentrism was seen as the product of logocentrism and phallocentrism (where the phallus stands in for male power and domination in a patriarchal society).

I focused on the body and the empowering significance of the maternal.

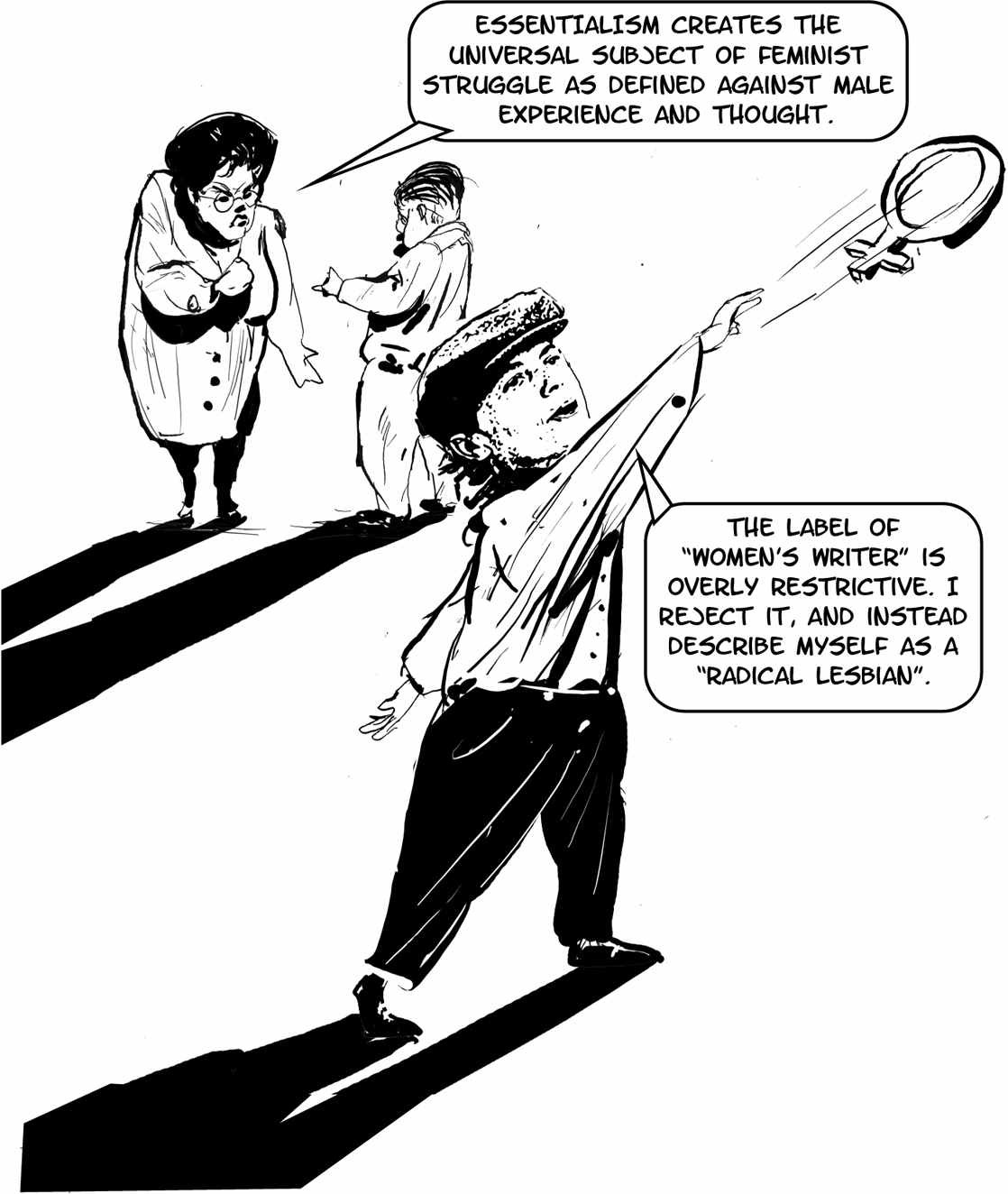

Other feminists, including Monique Wittig (1935—2003), challenged this focus on the body as biologically reductive and argued that the idea of écriture feminine was guilty of an essentializing universalism. Essentialism here refers to a focus on the social and psychological factors that constitute female experience and that are assumed to be common to all women.

ESSENTIALISM creates the universal subject of feminist struggle as defined against male experience and thought.

The label of “women’s writer” is overly restrictive. I reject it, and instead describe myself as a “radical lesbian”.

Relativists, by contrast, question the implied universality of the “category” of womanhood.

Partly as a result of these debates, contemporary feminism is hardly unified in approach. In the 1960s and 70s, one of the key debates among second-wave feminists concerned the possibility of an essential difference between writing by women and writing by men, expressing fundamental disparities between male and female experience.

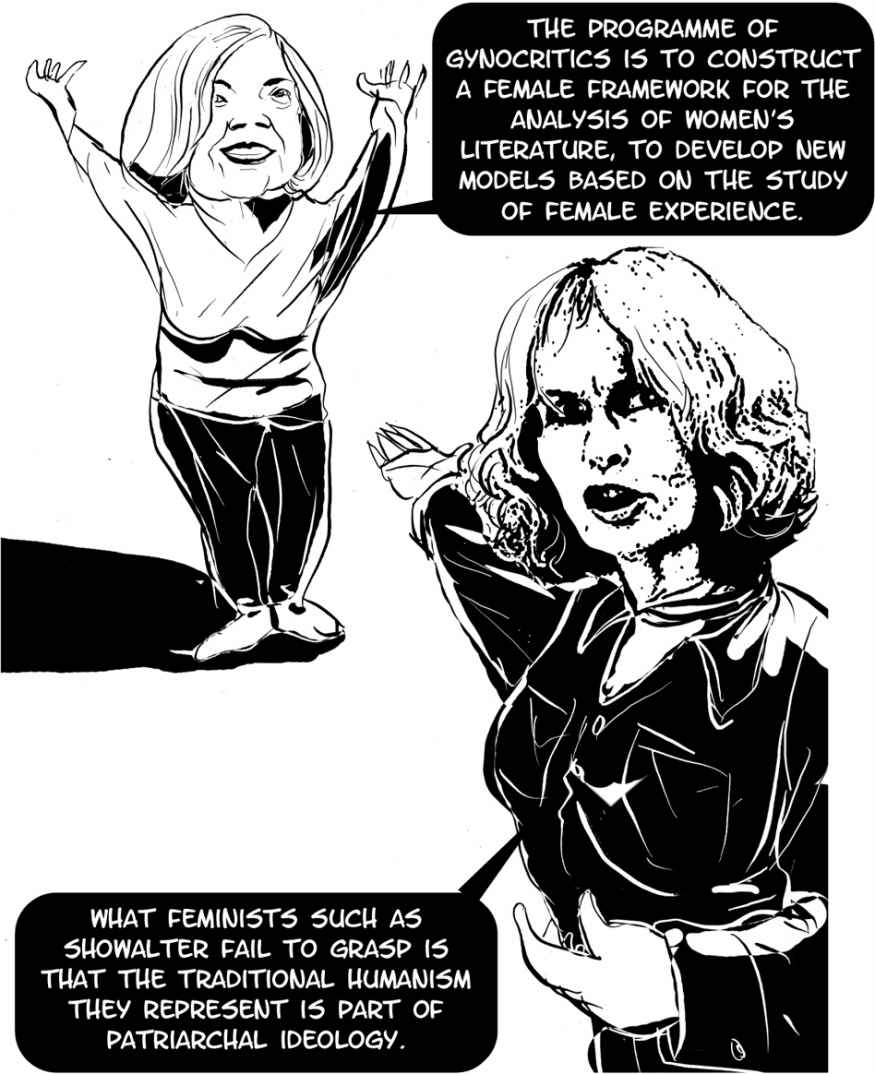

Showalter formulated the concept of “gynocriticism”:

The programme of gynocritics is to construct a female framework for the analysis of women’s literature, to develop new models based on the study of female experience.

What feminists such as Showalter fail to grasp is that the traditional humanism they represent is part of patriarchal ideology.

Toril Moi (b. 1953), in Sexual/Textual Politics (1985) responded to Showalter from a post-structuralist background, accusing her of essentialism.