Introducing Literary Criticism A Graphic - Owen Holland 2015

Some Versions of Historicism

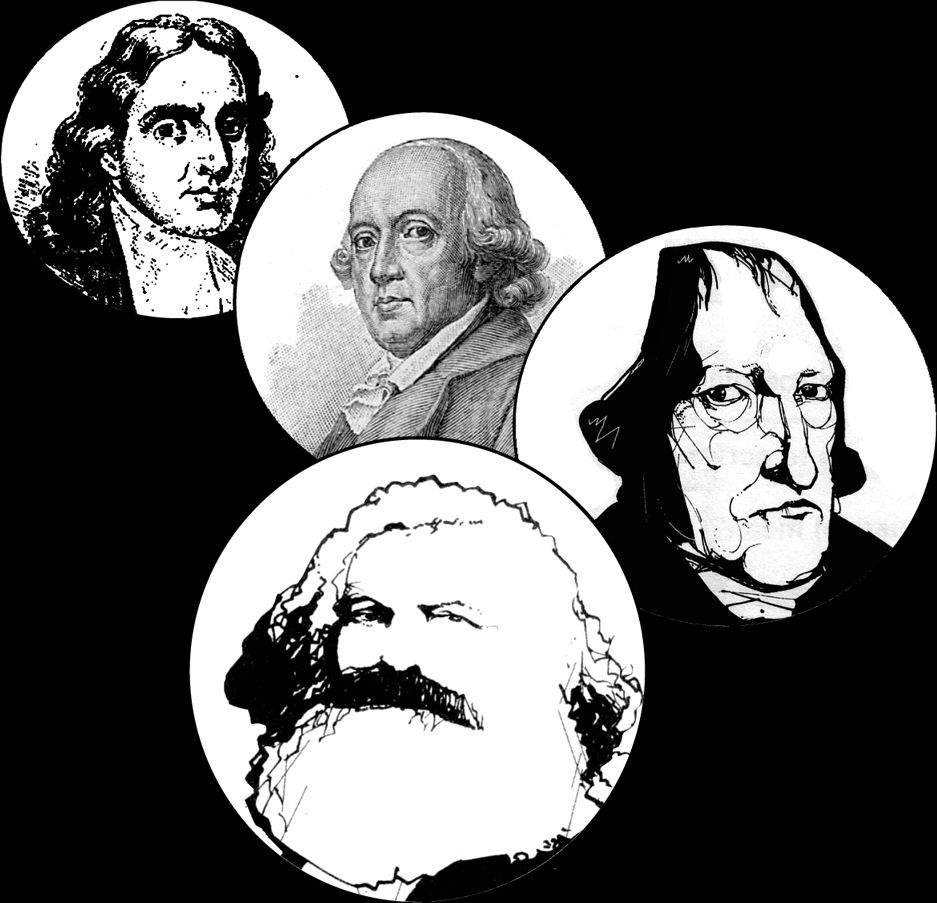

Historicism, or the historical view of literature, can be traced back the work of the 18th-century Italian philosopher Giambattista Vico (1668—1774) and the German philosopher and poet Johann Gottfried von Herder (1744—1803). Their historicism influenced later thinkers, including G.W.F. Hegel (1770—1831) and Karl Marx. The historical view of the work of classical writers and theorists questioned the universal basis of appreciation, across all times and places, focusing instead on the specificity of context and historical period (a kind of relativism*).

This historical way of thinking — which can be identified with the claim that knowledge itself is historically conditioned — was influential for much of the 18th and 19th centuries.

In the 1980s, the American literary critic Stephen Greenblatt (b. 1943) coined the term “New Historicism” to describe his own research on Elizabethan drama. The phrase first appeared in his introduction to a collection of essays he edited, The Power of Forms in the English Renaissance (1982). The majority of New Historicist criticism focuses on the Renaissance.

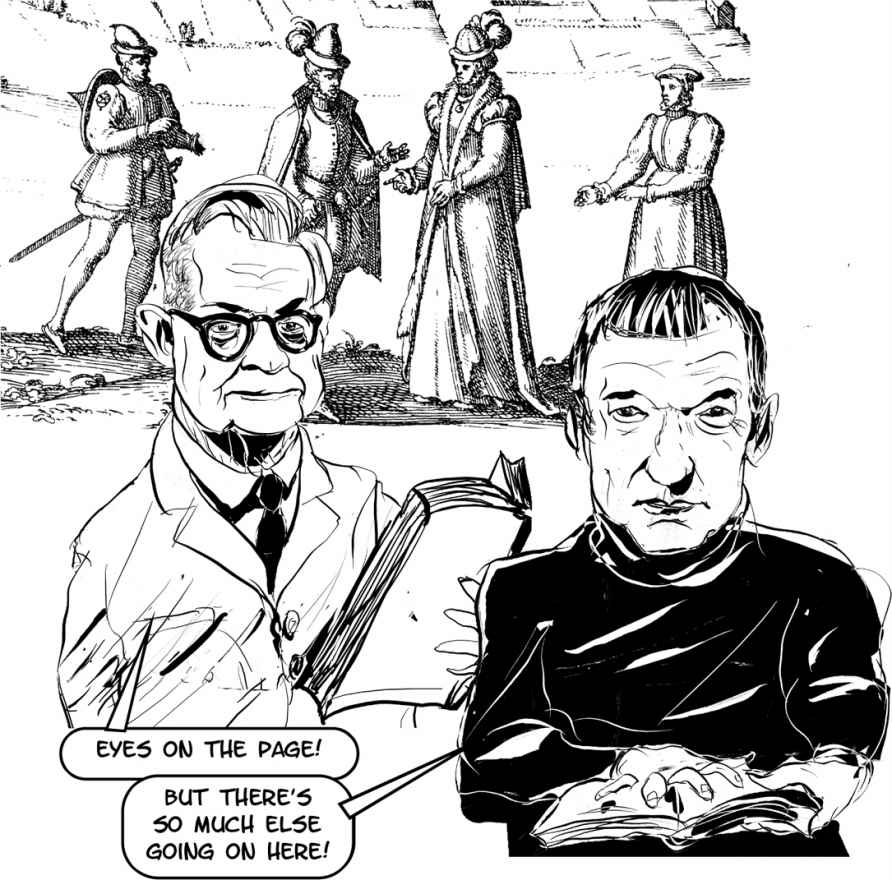

New Historicism can be understood as a partial return to a historical way of reading literature, in the wake of New Criticism’s formalist emphasis on the specificity of the literary text and the “words on the page”, which has often been accused of being a-historical.

Eyes on the page!

But there’s so much else going on here!

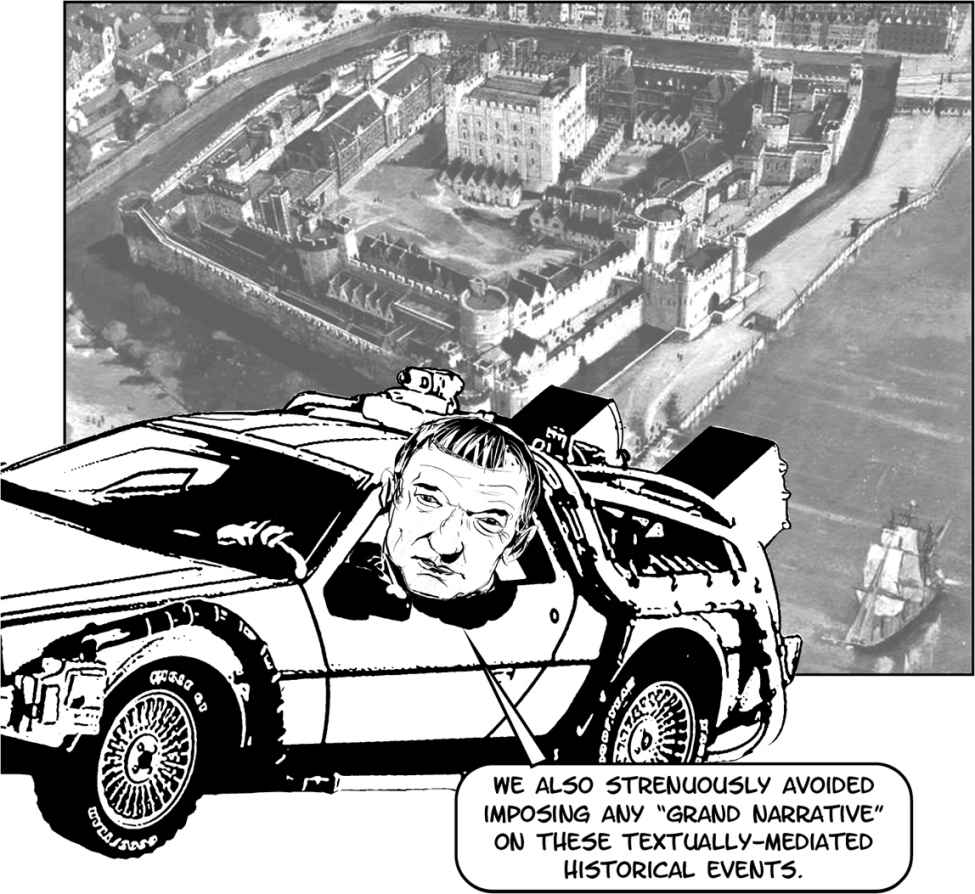

The dominant historicist trend in literary studies (which had been displaced by New Criticism), saw the critic’s function as an attempt to elucidate the connections between literary texts and their historical, biographical, social and cultural context. New Historicism inaugurated a “return” to the historical archive. This return, however, was mediated by the theoretical advances of structuralism and post-structuralism, particularly the work of Michel Foucault, whose studies in the history of discourses such as madness and sexuality offered a new, theoretically-informed way of navigating the vast swathes of archival material.

We need to go back in time to get the most from this text.

A New Historicist critic influenced by Foucault’s historical writing might trace patterns of discourse through an array of texts, selected not so much for their “literary” content, as for the way in which textuality* itself reveals the circulation of particular, historically determined discourses.

Tracing the circulation of a particular discourse can, in turn, reveal the structures of power that operate in a given social environment, as well as the ways in which certain kinds of textual and cultural practice might be mobilized to subvert such power-structures.

We also strenuously avoided imposing any “grand narrative” on these textually-mediated historical events.

One result of New Historicism has been to broaden the range and type of material that the literary critic might regard as a “legitimate” area of study, thus collapsing some of the previously accepted hierarchies between the “literary” and “non-literary” that had motivated previous critical practices.

Literary criticism begins to veer off, at this point, into cultural and intellectual history. Discourses of power might be just as visible in an obscure polemical tract or “minor” broadside ballad as in a “major” Shakespearean tragedy.