Introducing Literary Criticism A Graphic - Owen Holland 2015

From Literary Criticism to Literary Theory

In the latter half of the 20th century, New Criticism came under pressure. Its methods had proved useful as a teaching tool following the expansion of higher education after WWII, but this expansion was also one factor that led to a political and theoretical turn in literary criticism in the 1960s and 70s. Some of the major theoretical currents of the 20th century can be grouped into overarching movements — such as post-structuralism or New Historicism. But, as you will see, such labels are only partially appropriate.

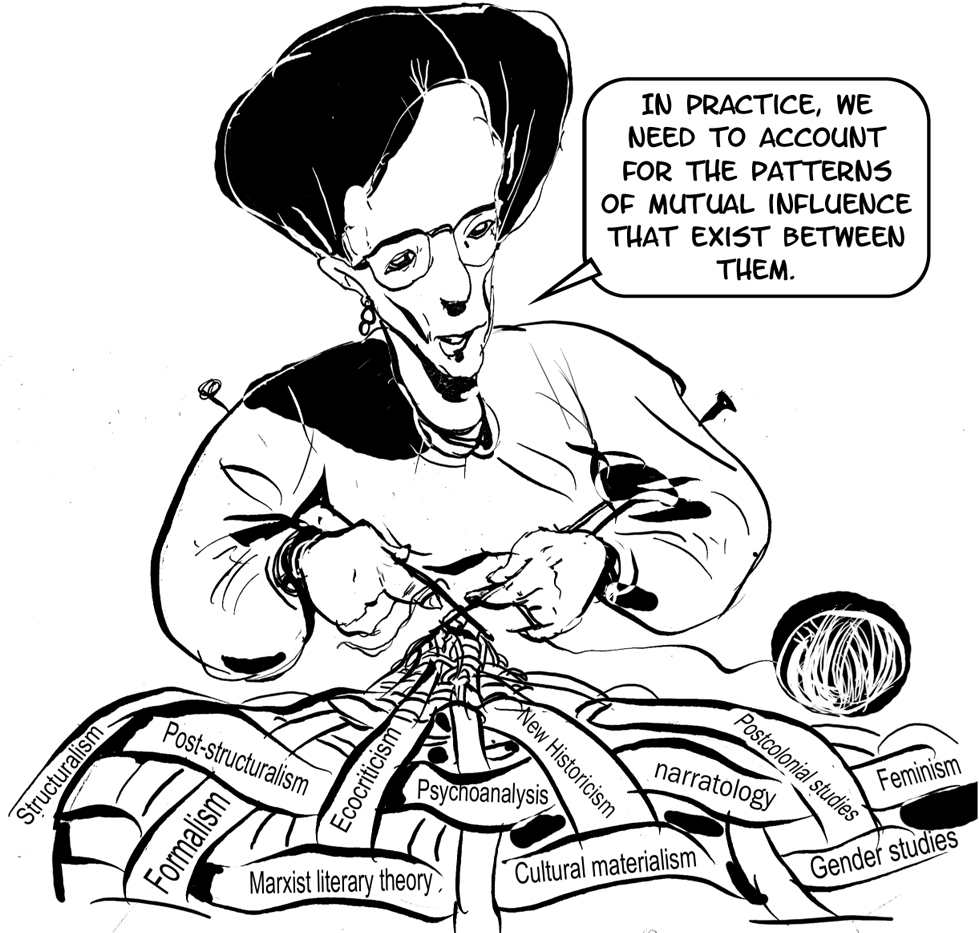

In this brief introduction, many of these critical methodologies and approaches are treated as discrete groups.

In practice, we need to account for the patterns of mutual influence that exist between them.

One of the most salient features of this theoretical turn in literary studies is the emphasis on interdisciplinarity, with its implied critique of narrow specialization. The interdisciplinary impetus has encouraged literary critics to engage with other disciplines, including philosophy and anthropology, and has often entailed a radicalization (and politicization) of approach. This returns us to the question of what might constitute the literary critic’s proper object of study.

Whereas some people reject theoretical approaches, Geoffrey Hartman (b. 1929) has argued that:

It is better to take the standpoint that criticism informed or motivated by theory is part of literary criticism (rather than of philosophy or an unknown science) and that literary criticism is within literature, not outside it.

In many of the theoretical currents described here, the issue of representation (or mimesis), which can be traced back to classical antiquity in the writings of Plato and Aristotle, reappears as a problem of ideological affinity, group identity and critical self-consciousness.