Introducing Literary Criticism A Graphic - Owen Holland 2015

Aestheticism

The two characters in Wilde’s dialogue, Gilbert and Ernest, engage in a discussion that elucidates the philosophy of aestheticism*, which Wilde had encountered in the work of the French novelist Théophile Gautier (1811—72), and in the teaching of the Oxford critic and essayist Walter Horatio Pater (1839—94).

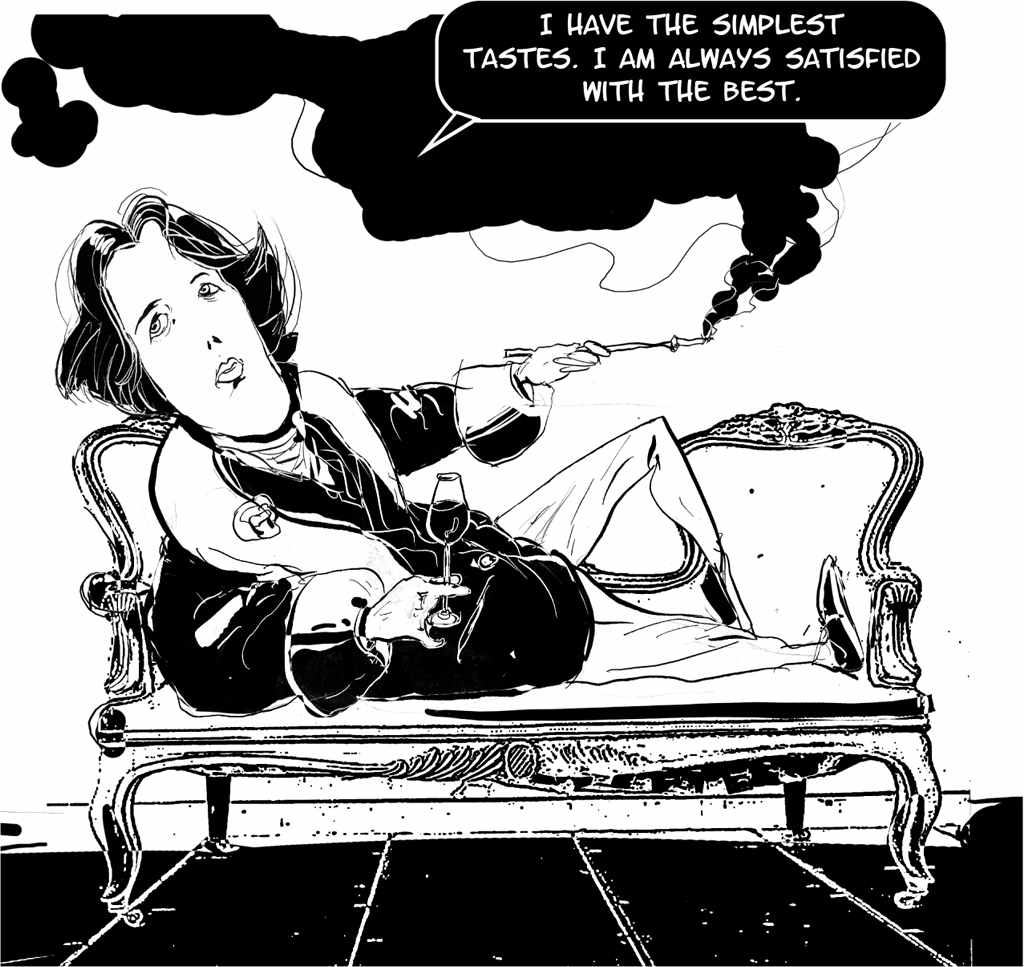

Wilde echoed Arnold’s emphasis on “disinterested curiosity” as a modus operandi for criticism, reiterating the classical distinction between active and contemplative kinds of life: the public life of social responsibility versus the life of study, or contemplation, removed from social duty. Wilde identified the aesthetic with the contemplative life. Aesthetics was thus seen as being entirely separate from the sphere of ethical imperative and moral purpose.

Action of every kind belongs to the sphere of ethics. The aim of art is simply to create a mood.

Aestheticism was a culmination of the anti-utilitarian spirit of the Romantic movement and the Victorian social criticism of Arnold and John Ruskin (1819—1900). But, unlike their predecessors, aesthetes denied any connection between art and morality or social concern.

Pater’s “Conclusion” to his Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873) was an important statement of fin de siècle aestheticism, which elevated the pursuit of ephemeral, sensuous experience and the “inward world of thought and feeling” as the highest purpose in life.

Pater’s elevation of immediate sensuous experience proved controversial enough to lead him to omit the conclusion from the second edition of The Renaissance. Pater seemed to have left the soul out of his account of human existence — scandalous in late Victorian Britain.

Pater looked to the poetry of Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837—1909) and the early poems of William Morris as expressions of his aesthetic philosophy. Wilde went further and embodied aestheticism in his ostentatious cultivation of a bohemian public persona, replete with green carnations and Egyptian cigarettes.

I have the simplest tastes. I am always satisfied with the best.

Thinking back to the distinction between Plato’s and Aristotle’s theories of mimesis, it is clear that Pater and Wilde are distant inheritors of the Aristotelian valorization of aesthetic pleasure. However, whereas Aristotle and later defenders of poetry emphasized the educational (and sometimes moral) value of pleasure, fin de siècle aesthetes sought pleasure purely for its own sake, denying all notions of utility and asserting the importance of doing nothing.