Introducing Literary Criticism A Graphic - Owen Holland 2015

Ancients and Moderns

Pope made clear his indebtedness to classical writers, alluding* or referring directly to Homer, Aristotle, Horace and Virgil, among others. This practice was part of a long-running critical debate in late-17th-century France and England between the so-called “ancients” and “moderns”.

The “ancients” looked to classical Greece and Rome as models for contemporary literary excellence (hence Pope’s decision to write in the Horatian mode). You might also look to the French playwright Jean Racine’s (1639—99) strict adherence to Aristotle’s “unities” for an example of a staunch “ancient”. The “moderns” looked instead to modern science as superior to and more enlightened than classical wisdom.

The quarrel broke out in France, revolving around a defence of heroic poems written by Jean Desmarets de Saint-Sorlin (1595—1676), which followed Christian rather than classical tradition. Nicholas Boileau’s L’Art Poétique (1674) set out the opposing case, defending classical traditions of poetry. The dispute continued into the 18th century.

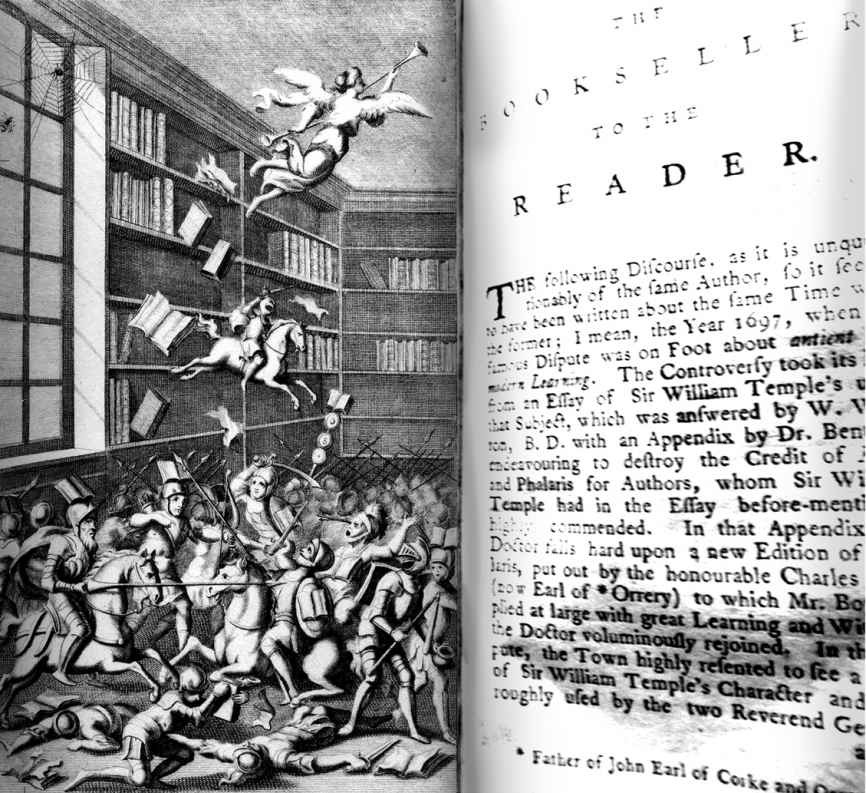

Both sides were satirized by Jonathan Swift (1667—1745) in A Tale of a Tub (1704) and its prologue “The Battle of the Books”, written in a style that parodies heroic poetry and depicts a battle between ancient and modern books in St James’s Library.

The most notable English authors who followed classical models and rules were Ben Jonson (1572—1637), John Dryden (1632—1700), Pope, Swift, Joseph Addison (1672—1719) and Dr Johnson (1709—84).