Introducing Literary Criticism A Graphic - Owen Holland 2015

Defenders of Poetry: Sidney and Shelley

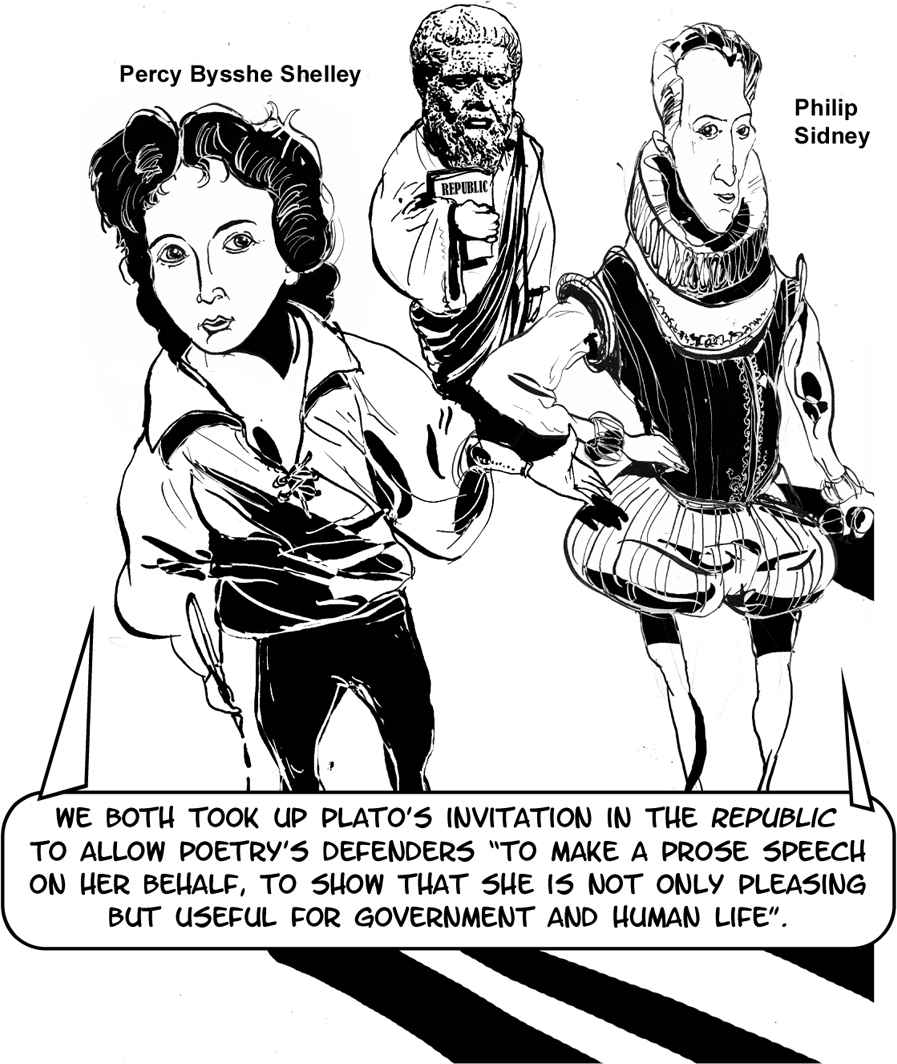

Brecht responded to Aristotle as a drama practitioner and a playwright. Other “practitioners”, including poets like Philip Sidney (1554—86) and Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792—1822), were influenced by Aristotle’s defence of the educational value of aesthetic pleasure when writing their own defences of poetry. Both were responding, creatively and wittily, to attacks on the value and status of poetry.

Sidney wrote against 16th-century puritans, defending poetry and drama against accusations of blasphemy. Shelley responded to Thomas Love Peacock’s (1785—1866) essay “The Four Ages of Poetry” (1820), in which Peacock claimed that poetry was being overshadowed by science.

We both took up Plato’s invitation in the Republic to allow poetry’s defenders “to make a prose speech on her behalf, to show that she is not only pleasing but useful for government and human life”.

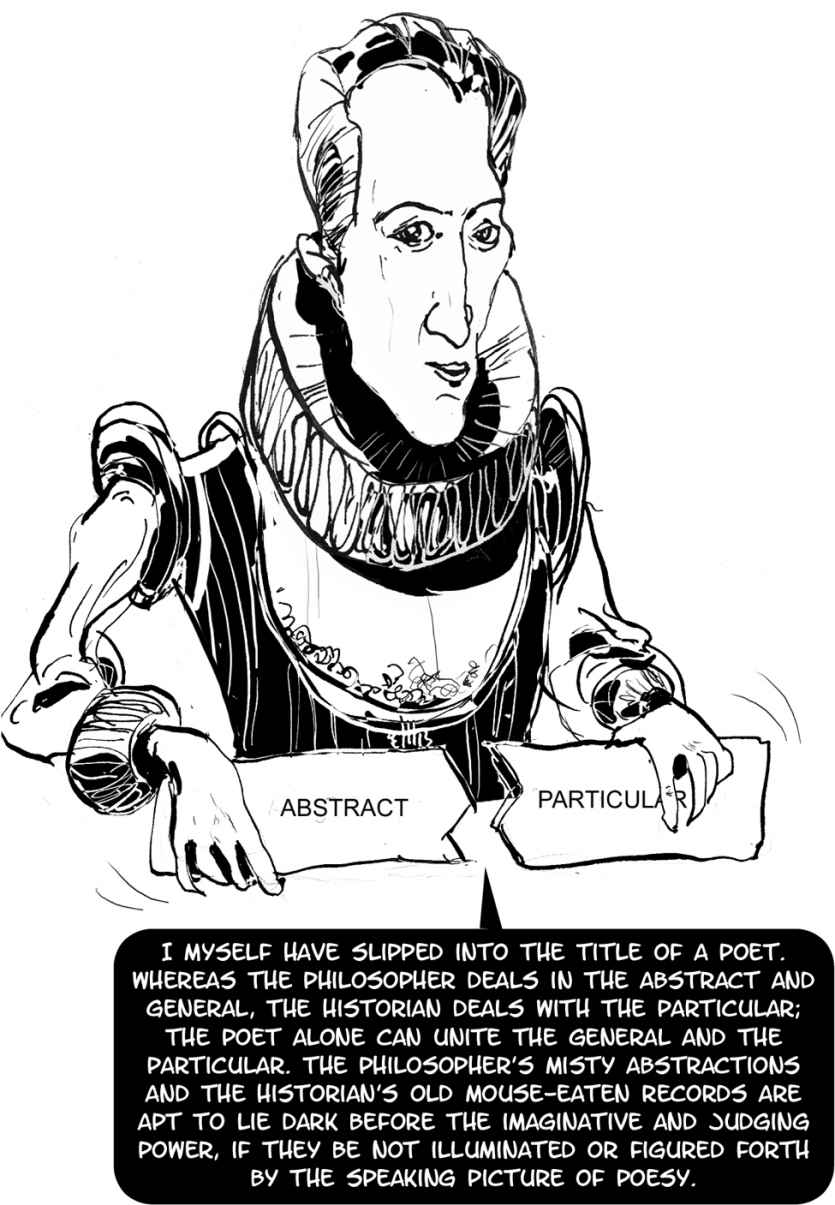

In Sidney’s Defence of Poesy, also known as his Apologie for Poetrie, (1581) he offered a playful, but serious, estimation of the relative merits of history, philosophy and poetry.

I myself have slipped into the title of a poet. Whereas the philosopher deals in the abstract and general, the historian deals with the particular; the poet alone can unite the general and the particular. The philosopher’s misty abstractions and the historian’s old mouse-eaten records are apt to lie dark before the imaginative and judging power, if they be not illuminated or figured forth by the speaking picture of poesy.

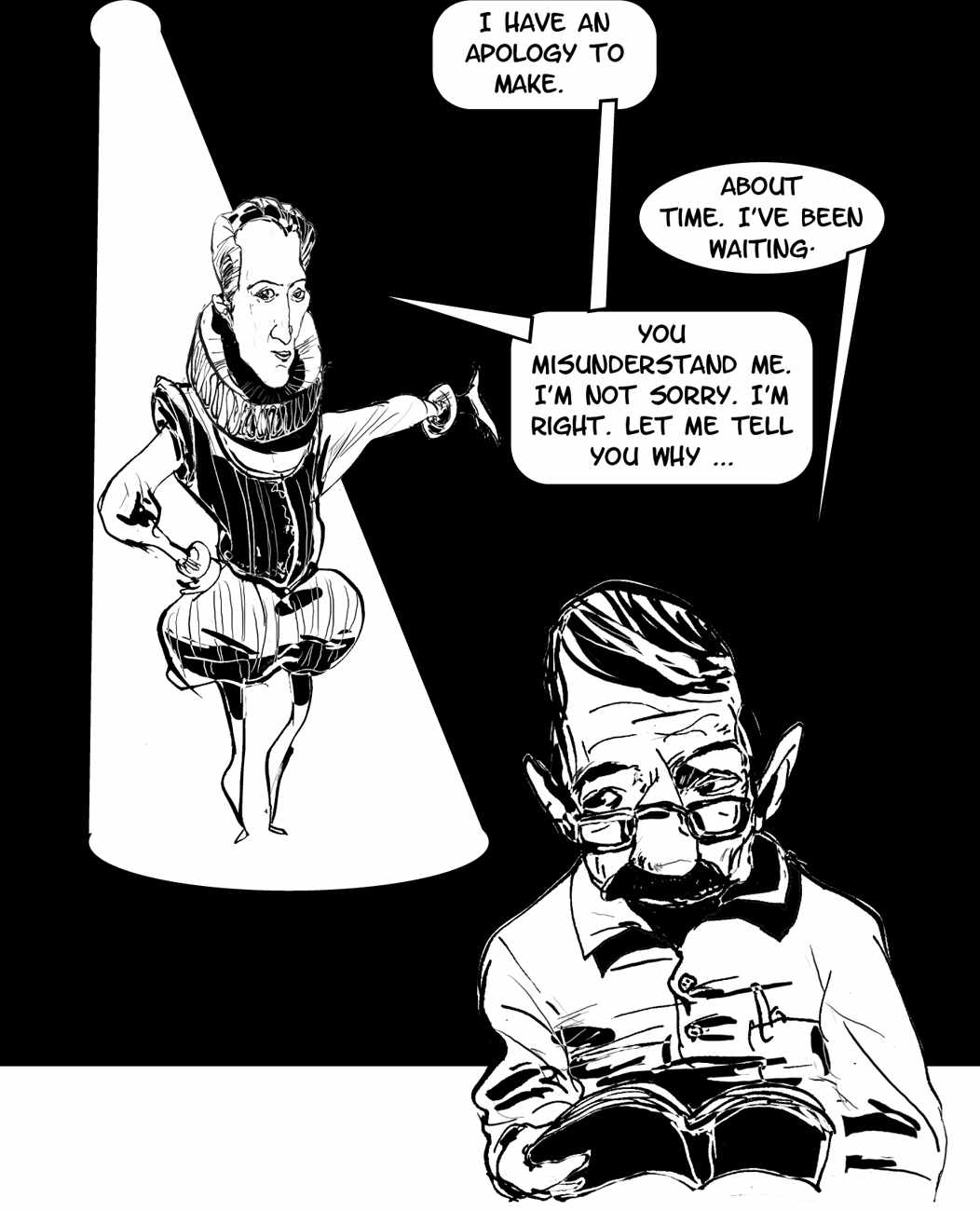

In the sense meant by Sidney, an apology is a formal defence or justification of one’s position, rather than an expression of regret.

I have an apology to make.

About time. I’ve been waiting.

You misunderstand me. I’m not sorry. I’m right. Let me tell you why …

Sidney sustained his own argument with reference to classical poets, including Homer, Dante, Boccaccio and Petrarch.

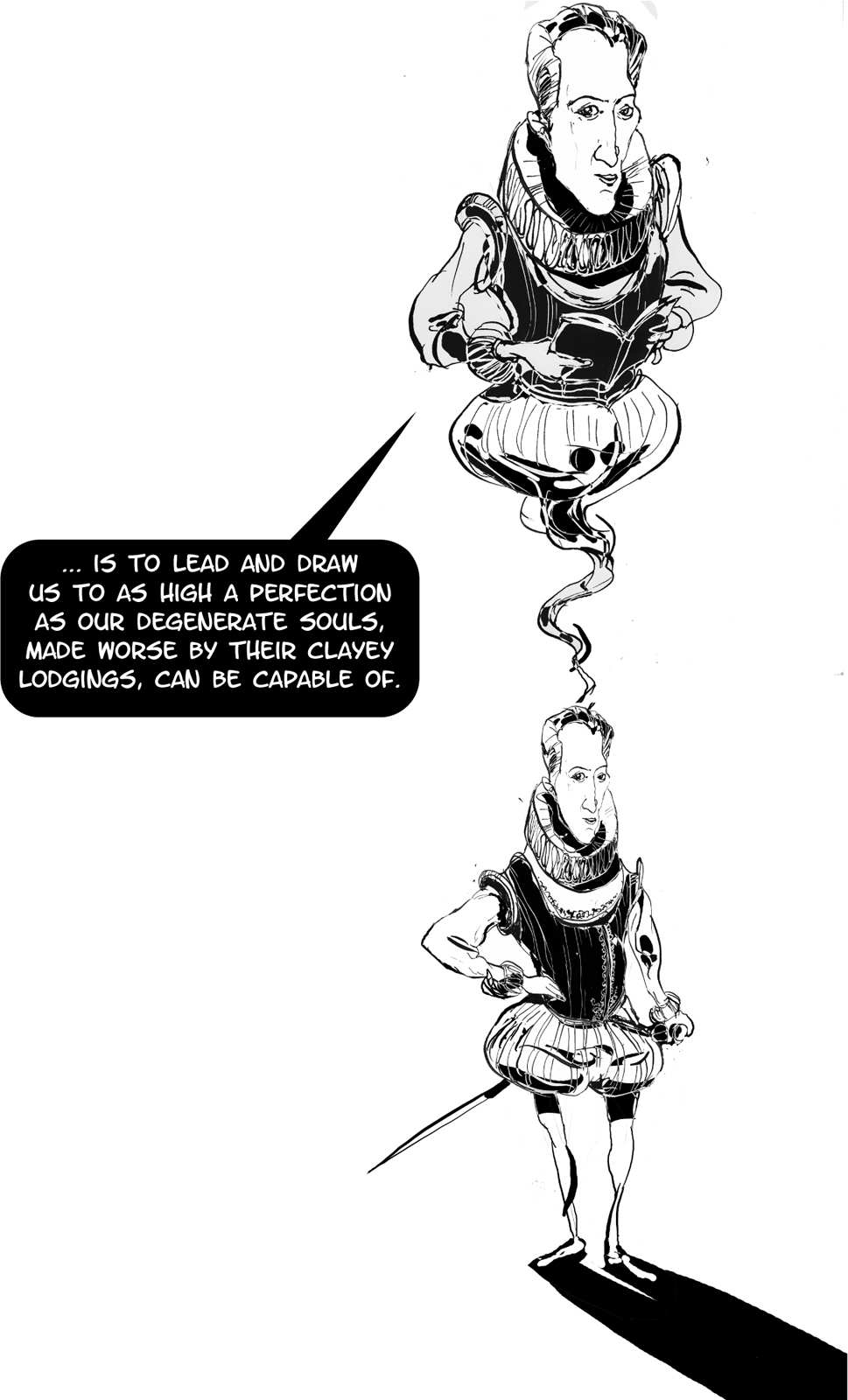

Sidney also echoed the discussion of mimesis found in Plato and Aristotle, identifying “feigning” (making, or representation) with the work of a poet and emphasizing poetic imitation as a means of “delightful teaching”. According to Sidney, poetry can purify wit, enrich memory, enable judgement and enlarge conceit. Its aim …

… is to lead and draw us to as high a perfection as our degenerate souls, made worse by their clayey lodgings, can be capable of.

It’s clear that Sidney was more in sympathy with Aristotle’s defence of mimesis than he was with Plato’s suspicious dismissal, which is hardly surprising given that Sidney’s “apologie” for poetry was also, implicitly, a defence of his own status as a poet.

Sidney offered two important definitions of the poet. First, citing the Latin word for poets, vates (which means “diviner”, “foreseer” or “prophet”), Sidney identified poets with “divine force”, recalling one of Plato’s early dialogues, Ion. Second, he noted that the English word “poet” derives from the Greek poiein, meaning “to make”.

Only the poet, lifted up with the vigour of his own invention, doth grow, in effect, into another nature, in making things either better than nature bringeth forth or, quite anew, forms such as never were in nature.

In his “A Defence of Poetry”, written in 1821 but first published in 1840, Shelley suggested that poetry has cognitive, as well as aesthetic, value and offers a particular way of knowing about the world, distinct from knowledge gained by reason. On this basis he maintained that “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world”. Shelley also claimed that poetry serves a morally instructive role:

The great instrument of moral good is the imagination; and poetry administers to the effect by acting upon the cause. Poetry enlarges the circumference of the imagination by replenishing it with thoughts of ever new delight.

The educational function of poetry is here seen to have a simultaneously humanizing influence.

Shelley did not, however, see the moral function of poetry as straightforwardly didactic, or moralizing. Shelley instead defended the value of poetry with recourse to some particularly arresting (if mixed) metaphors*.

A Poet would do ill to embody his own conceptions of right and wrong, which are usually those of his time and place, in his poetical creations, which participate in neither.

Poetry is a sword of lightning, ever unsheathed, which consumes the scabbard that would contain it.

Poetry lifts the veil from the hidden beauty of the world, and makes familiar objects be as if they were not familiar.