USA Literature in Brief - Kathryn VanSpanckeren 2007

The Rise of Realism

The U.S. Civil War (1861-1865) between the industrial North and the agricultural, slave-owning South was a watershed in American history. Before the war, idealists championed human rights, especially the abolition of slavery; after the war, Americans increasingly idealized progress and the “self-made man.” This was the era of the millionaire manufacturer and the speculator, when the Darwinian theory of biological evolution and the “survival of the fittest” species was applied to society and seemed to sanction the sometimes unethical methods of the successful business tycoon.

Business boomed after the war. The new intercontinental rail system, inaugurated in 1869, and the transcontinental telegraph, which began operating in 1861, gave industry access to materials, markets, and communications. The constant influx of immigrants provided a seemingly endless supply of inexpensive labor as well. Over 23 million foreigners—German, Scandinavian, and Irish in the early years, and increasingly Central and Southern Europeans thereafter—flowed into the United States between 1860 and 1910. In 1860, most Americans had lived on farms or in small villages, but by 1919 half of the population was concentrated in about 12 cities.

Problems of urbanization and industrialization appeared: poor and overcrowded housing, unsanitary conditions, low pay (called “wage slavery”), difficult working conditions, and inadequate restraints on business. Labor unions grew, and strikes brought the plight of working people to national awareness. Farmers, too, saw themselves struggling against the “money interests” of the East. From 1860 to 1914, the United States was transformed from a small, agricultural ex-colony to a huge, modern, industrial nation. A debtor nation in 1860, by 1914 it had become the world’s wealthiest state. By World War I, the United States had become a major world power.

As industrialization grew, so did alienation. The two greatest novelists of the period—Mark Twain and Henry James—responded differently. Twain looked South and West into the heart of rural and frontier America for his defining myth; James looked back at Europe in order to assess the nature of newly cosmopolitan Americans.

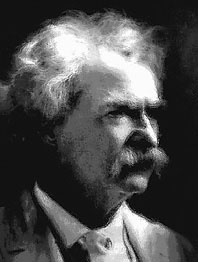

Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) 1835-1910

Illustration by Thaddeus A. Miksinski, Jr.

Samuel Clemens, better known by his pen name of Mark Twain, grew up in the Mississippi River frontier town of Hannibal, Missouri. Ernest Hemingway said that all of American literature comes from one great book, Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Early 19th-century American writers tended to be too flowery, sentimental, or ostentatious—in part because they were still trying to prove that they could write as elegantly as the English. Twain’s style, based on vigorous, realistic, colloquial American speech, gave American writers a new appreciation of their national voice. Twain was the first major author to come from the interior of the country, and he captured its distinctive, humorous slang and iconoclasm.

For Twain and other American writers of the late 19th century, realism was not merely a literary technique: It was a way of speaking truth and exploding worn-out conventions. Thus it was profoundly liberating and potentially at odds with society. The most well-known example is his story of Huck Finn, a poor boy who decides to follow the voice of his conscience and help a Negro slave escape to freedom, even though Huck thinks this means that he will be damned to hell for breaking the law.

Twain’s masterpiece, which appeared in 1884, is set in the Mississippi River village of St. Petersburg. The son of an alcoholic bum, Huck has just been adopted by a respectable family when his father, in a drunken stupor, threatens to kill him. Fearing for his life, Huck escapes, feigning his own death. He is joined in his escape by another outcast, the slave Jim, whose owner, Miss Watson, is thinking of selling him down the river to the harsher slavery of the deep South. Huck and Jim float on a raft down the majestic Mississippi, but are sunk by a steamboat, separated, and later reunited. They go through many comical and dangerous shore adventures that show the variety, generosity, and sometimes cruel irrationality of society. In the end, it is discovered that Miss Watson had already freed Jim, and a respectable family is taking care of the wild boy Huck. But Huck grows impatient with civilized society and plans to escape to “the territories”—Indian lands.

The ending gives the reader another version of the classic American “purity” myth: the open road leading to the pristine wilderness, away from the morally corrupting influences of “civilization.” James Fenimore Cooper’s novels, Walt Whitman’s hymns to the open road, William Faulkner’s The Bear, and Jack Kerouac’s On the Road are other literary examples.

Henry James 1843-1916

Courtesy Library of Congress

Henry James once wrote that art, especially literary art, “makes life, makes interest, makes importance.” James’s fiction is the most highly conscious, sophisticated, and difficult of its era. James is noted for his “international theme”—that is, the complex relationships between naïve Americans and cosmopolitan Europeans.

What his biographer Leon Edel calls James’s first, or “international,” phase encompassed such works as The American (1877), Daisy Miller (1879), and a masterpiece, The Portrait of a Lady (1881). In The American, for example, Christopher Newman, a naïve but intelligent and idealistic self-made millionaire industrialist, goes to Europe seeking a bride. When her family rejects him because he lacks an aristocratic background, he has a chance to revenge himself; in deciding not to, he demonstrates his moral superiority.

James’s second period was experimental. He exploited new subject matters—feminism and social reform in The Bostonians (1886) and political intrigue in The Princess Casamassima (1885). In his third, or “major,” phase James returned to international subjects, but treated them with increasing sophistication and psychological penetration. The complex and almost mythical The Wings of the Dove (1902), The Ambassadors (1903) (which James felt was his best novel), and The Golden Bowl (1904) date from this major period. If the main theme of Twain’s work is the often humorous difference between pretense and reality, James’s constant concern is perception. In James, only self-awareness and clear perception of others yields wisdom and self-sacrificing love.